This article will chronicle a number of experiences I've encountered, both incidentally and intentionally, since my younger years. Given my background and contributions, I wish to shed some light on the subject of human trafficking without explicitly identifying any individuals or organizations involved. I've spent several years working in roles deeply connected to the refugee crisis, conducting thousands of interviews, notably with refugees from Afghanistan and Iran. Additionally, I had the opportunity to witness firsthand the circumstances of Afghan refugees during my time in Iran. Additionally, I hail from Çanakkale/Assos, an area which has seen the highest levels of human trafficking since the onset of the refugee crisis.

Assos: A Gateway to Europe

Years ago, Assos was a community whose people mainly fished and cultivated olives. The area lies in close proximity to Lesbos, a major hub in the current refugee crisis. My childhood was filled with fishermen's tales from this place. Two decades ago, a fisherman, whose son later became a notorious smuggler, was arrested by the Greek Coast Guard for straying too close to the island. He returned home after three days, and I remember his story captivating my youthful mind. As a descendant of a family that migrated during the 1923 population exchange, my curiosity was naturally drawn to Lesbos. Similar stories were also enjoyed by villagers, often becoming topics of banter in local coffeehouses.

With time, Assos evolved from a place without basic utilities like electricity and water, into a much-sought-after tourist hotspot. Villagers sold their lands to city dwellers from Istanbul at prices far below their worth. Many of these lands, owned by fishermen, were seaside properties coveted by hoteliers aiming for coastal establishments. Acquisitions were done using either financial incentives or intimidations, and I watched this transition firsthand. Many villagers who parted with their lands also lost their olive groves in the process. They eventually grasped the enormity of their mistake, but it was a realization that came too late. Once landowners, they ended up unemployed, squandered their money, and then started working as servants in the hotels and homes constructed on their former lands by the Istanbulites. While some youngsters migrated to other cities, others remained, living in poverty.

Looking at these events, naturally, the sociological context of the issue becomes clear. When the refugee crisis emerged, human smuggling morphed into a new trade in border areas, and Assos held a distinct role as a conduit to Europe. And naturally, the locals accepted the lucrative job offers worth millions of euros. They were familiar with the sea and the geography; all that remained was to play their part, which they did. The unemployed youth of the past suddenly became millionaires, possessing cars, homes, and more. Today, many have left the country to reside in Europe.

I want to delve a little deeper into this "job". Based on information gathered from refugees and locals, smugglers charged between €1500 to €2000 per person. Considering that an average zodiac boat could transport 40 people, each transit earned about 80-100 thousand euros. Others in the network, like sellers of counterfeit life jackets, vehicle renters, and lookouts for the smugglers, also made substantial profits. In no time, the business morphed into an industry. Even barbers were making and selling fake life jackets to refugees. A professional photographer in Çanakkale informed me that he was offered $2000 just to act as a lookout for the smugglers. His only task was to drive ahead of the smugglers, and if stopped by the police/military police, he would move his vehicle forward to alert the smugglers following behind.

Eventually, smugglers began renting local restaurants and hotels. Zodiac boats were concealed in these establishments, providing them a convenient base for their operations. One such location was the hotel behind our house (where I snapped the photo above). In 2015, while we were away, they hid a zodiac boat in our backyard. My father stumbled upon it during a visit to the house. He reported it to the authorities, but the response was dismissive as the officer remarked that their storage was already overflowing with similar boats.

From 2014 to 2017, the area witnessed an unparalleled human tragedy. A close friend, working as a Persian translator for an NGO assisting refugees in Çanakkale, often had the heart-wrenching task of interpreting for relatives trying to identify bodies of drowned individuals. The psychological toll of this job was such that it took him years to recover.

Despite working a refugee-related job a thousand kilometers away from Çanakkale, the area's connection to the refugee crisis was never far from my purview. Many refugees from Afghanistan either had relatives in Çanakkale or used it as a transit point to Lesbos. Some were apprehended by the police and deported back to the city where I was working. Interestingly, while many refugees struggled to pronounce the names of their registration towns, Çanakkale was a name they knew well.

"Afghan Markets" and Their Role

Turkey, as we know, is a long and rectangular country. I have previously discussed the happenings on its western flank, and now I aim to shed light on the eastern half. Most Afghans reside in Iran under abysmal conditions. Numerous children are deprived of their right to education, and the most undesirable jobs are invariably handed to Afghans. Driven by both the extreme living conditions in Iran and the aspiration to reach Europe, many embark on an unlawful journey to Turkey.

This voyage typically commences at the bus terminal in Tehran's Azadi Square, where refugees make their way to border towns (Maku being the most common destination). Upon arrival, they're met by Kurdish smugglers with connections on both sides of the border, who facilitate their passage into Turkey. They then make their way to Istanbul using the D100 highway, effectively avoiding security checkpoints in Ankara. A significant number of these refugees are intercepted en route and directed to various Turkish provinces for registration.

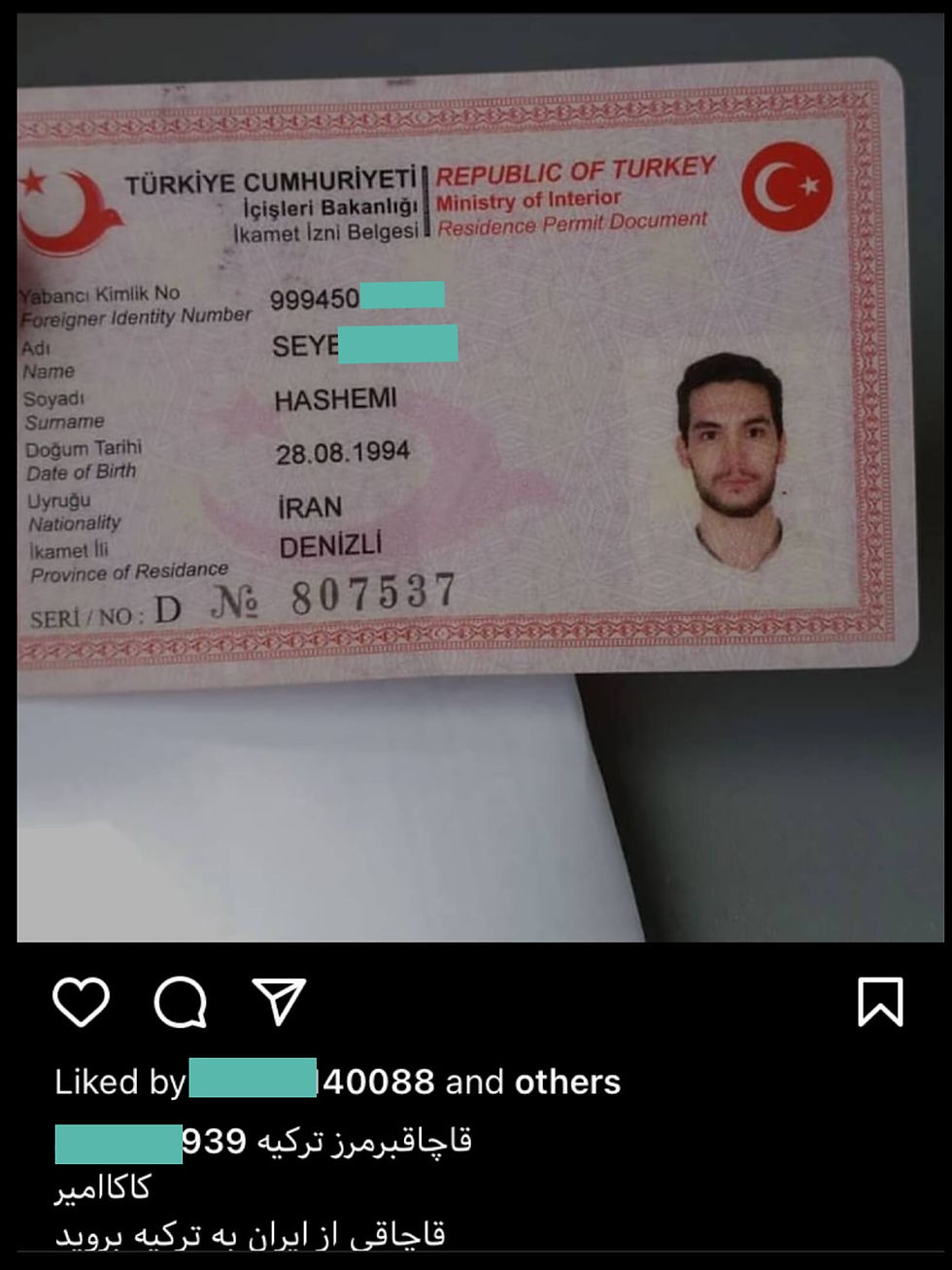

Once in Istanbul or the other assigned provinces, these refugees find employment and begin to settle in. In time, they discover grocery stores run by fellow Afghans in their city. These establishments, known colloquially as "Afghan Markets," sell everyday items like cigarettes and rice, all of which are illegally imported from Iran. However, the primary function of most of these markets is to connect incoming refugees with human smugglers. Spread across nearly every city in Turkey, these markets serve as crucial contact points for refugees looking to cross into Europe. They also offer services like money transfer to Iran, sales of a drug named "nas," and provision of counterfeit documents, including fraudulent travel permits and passports.

Final Observations

I'd like to take a moment to elaborate on "nas". Though not officially classified as a drug, it is widely consumed by Afghans as an alternative to cigarettes. There are even allegations of families using it to soothe crying infants. Furthermore, it's allegedly administered to children as a means to deceive officials in immigration offices or various aid institutions. By asserting "my child is sick, please help" (in Persian: "Dokhterem/Pserem mareeze, komakam konid") and showcasing a seemingly ill child, they seek to expedite their proceedings and play on people's emotions. With or without nas, this phrase is so overused that it has become somewhat of an inside joke among those working in NGOs and government institutes.

1. The smugglers ask the people, "guys, how is the bread (food)" then they answer "very good". The smugglers ask the people again, "is there any problem" and they reply, "no".

2. In this video, they express how happy they are to reach Turkey.

3. In this video, the smuggler asks, "whose guest are you?" and "how many times you guys get food" then the refugees answer his name and three times a day.

4. These are other examples of ads.

5. And these are the pictures of the fake document ads.

I actually have a lot to write about this topic. Maybe I will write more in future posts. I don't even want to get into the stories of people and children who died, were murdered, or were raped along the way. The fact is pretty clear: this is a multifaceted problem involving tragedies throughout and a problem with stories full of tears and pain.

Good job, thanks.